Humans have documented visa approximately 1,470 square miles, or only 0.001 percent, or the deep background fund, according to a new study. That is a bit larger than the size of Rhode Island.

The report, published on Wednesday in the journal Science Advances, reaches the nations discuss whether to pursue industrial mining of the Marine Fund for Critical Minerals.

Some scientists argue that so little is known about the underwater world that more research is needed on the deep seabed to advance with extractive activities.

“More information is always beneficial, so we can make more informed and better decisions,” said Katy Caty Croff Bell, a deep oceaner who directed the study and is the founder of the Ocean Discovery League, a non -profit group that promotes the exploration of marine marinas.

Learning more about the deep sea is essential to understand how climate change and human activities are affecting the oceans, he said. But the study also highlights the fundamental emotion of exploration that drives many marine scientists.

“You can imagine what is in the rest of 99,999 percent,” said Dr. Bell.

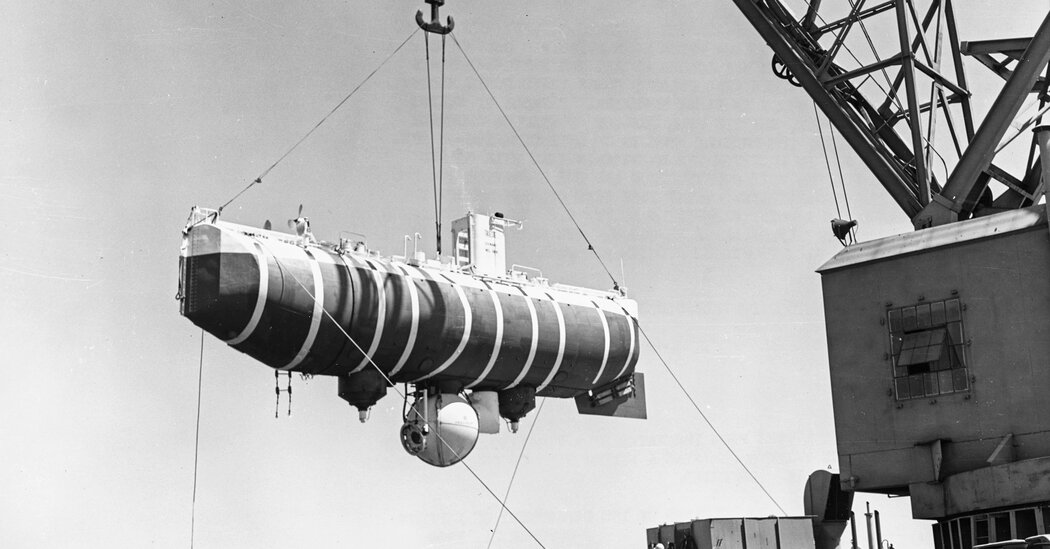

The era of visual documentation included in the Begen study in 1958, with the submersible trieste of deep water. The images collected since then allow biologists to discover new organisms and observe how they interact with each other and their environments, providing information about oceanic ecosystems.

Bringing deep water organisms to the surface to study is a challenge. Adapted for high pressures, few animals, if any, survive the trip, so the photos and videos are crucial.

“There are some habitats that you can’t try from a ship,” said Craig McClain, a marine biologist at the University of Louisiana who did not participate in the study. “You have to go there in a ROV and do it,” he said, referring to vehicles remotely operated.

Obtaining Seaflor images also helps geologists. Before the advent of submarine vehicles operated remotely and CREDO’s submersible, the researchers had a more limited approach: leave a large bucket of a ship, drag it, drag it up and see what was inside.

“They would simply have a mixture of rocks and try to solve it, without context,” said Emily Chin, a geologist at the Scripps Oceanography Institution that did not participate in the new study. “It’s like people studying meteorites, trying to understand one process on another planet.”

Seeing marine rock outcrops in photos and videos has allowed scientists to learn how fundamental land processes work. It also helps companies evaluate possible sites for mining and oil and gas activities.

But reaching the seabed is an expense, both in funds and in time. Explore a square kilometer or a deep seabed can cost between $ 2 million to $ 20 million, Dr. Bell estimated. The dives can take years to prepare, and just hours to go wrong. And once an immersion is underway, it progresses slowly. A rover tied to a ship has a limited radius of exploration, moving in a tracking and relocating the ship is tedious.

With so many barriers, Dr. Bell wanted to know how much seabed we have seen and how much is left to explore.

Dr. Bell and her collaborators collected more than 43000 records of deep water dives and evaluated the photos and videos that have been collected, estimating how much marine background area documented the immersions.

Together, they estimated that between 2,130 and 3,823 square kilometers of the deep background fund they have bone. That works at approximately 0.001 percent of the entire deep seabed.

“I knew I was going to be small, but I’m not sure if I expected it to be so small,” Dr. Ir. Bell said. “We have been doing this for almost 70 years.”

The study excludes ownership immersions where data is not publicly warned, such as military operations or oil and gas exploration. Even if those increased the documented area by order of magnitude, Dr. Ir. Bell said: “I don’t think it’s enough to move the needle.”

Much of what the deep sea marine biologists know on the seabed is based on that small fraction. The situation is similar to extrapolar information from a smaller area that Houston to all terrestrial surfaces of the Earth, say the authors.

The study also found that the country of high income led 99.7 percent of all deep dives, with the United States, Japan and New Zealand leading the lists. Most of the dives were within 200 nautical miles of those three countries. That means that the dives are led by a small group of countries, potentially biased what is investigated and where, the authors said.

“There are many people around the world who have experience in deep water,” said Dr. Bell. “They simply do not have the tools to be able to make the son of research and exploration they want to do.”

The dives tend to be in the same areas, such as the Mariana trench or the Monterey cannon, or point to the same child of interest characteristics, such as hydrothermal vents, according to the study. And since the 1980s, most deep dives have a leg in lower and coastal waters. That leaves many areas in the depths of the unexplored sea.

“The study is a good evaluation of where we are and, literally, where we need to go in the deep sea,” said Dr. McClain.